My four earlier blog posts about the Japanese language books Album of Management Revolution, Taiichi Ohno’s Records: Founder of the Toyota Production System, The Origin of Toyota’s Strength: Taiichi Ohno’s Kaizen Spirit, and Taiichi Ohno and the Toyota Production System, offer much to reflect on about Taiichi Ohno’s thinking and his work as a genba teacher.

If you were taught directly by Taiichi Ohno, you were taught to think differently. Specifically, you were taught to think about how to solve problems in ways that are opposite to how people would typically solve the same or similar problem. The key word here is opposite. To do that, you need to develop your curiosity about work — what work is and how work is performed by humans, machines, or and both humans and machines. Most people do not have such curiosity.

For a long time, people have been using so-called “Lean tools” to augment efforts to solve problems mostly in the usual way that problems are solved, not in opposite ways. The result, predictably, is far less improvement than could otherwise be achieved.

The great Henry Gantt said: “The usual way of doing a thing is always the wrong way.” That would include both how Lean tools are used (likely wrong) as well as the method of problem-solving that Lean tools are supposed to help with (also likely wrong). The key word here is usual.

If you were taught directly by Taiichi Ohno, you would be taught to use your intelligence and creativity, which you might not know that you have, and use these to develop ingenuity to solve problems on the genba. If you defended “the usual way of doing a thing,” did not use your imagination, or did not think of opposite ways to solve the problem, you would get scolded. Why? To get ahead in a competitive business environment you must not do what everyone else does when it comes to problem-solving.

Lean world often cites “underutilized talent” as one of the eight types of waste (though there are many more than just eight). This can also mean “underutilized intelligence.” But it is apparent that “not using intelligence,” rather than “underutilized intelligence,” is more accurate. The phrase “underutilizing talent” is not useful because talent can be underutilized in the context of Gantt’s “the usual way of doing a thing” or Ohno’s “opposite ways.” In the former, intelligence is not used if the outcome is “always the wrong way.”

Toyota people will tell you that the Toyota Production System also means “Thinking Production System.” What does thinking mean? If your thinking is, by way of habit, rigidly aligned with “the usual way of doing a thing,” then you are not thinking. You are just doing what you have always done. You are doing things without thinking.

Taiichi Ohno apparently spent a lot of time scolding his disciples (and others) on the genba because it was difficult for them to think of opposite ways to solve problems. Additionally, Ohno-san seems to have not given much guidance on what the desired solution should look like. His disciples had to think for themselves and figure it out.

Thinking in opposite ways is not contrarian in the sense of someone who reflexively rejects conventional wisdom and takes opposing views for everything they encounter. That is not what Ohno-san taught. His primary objective was to help Toyota survive. To do that he developed people’s intelligence, creativity, and ingenuity so that opposite ways of thinking were not automatically ruled out as potential solutions to difficult problems. Instead, Ohno-san encouraged his disciples to consider and test opposite ways on the genba via trial and error to see what would happen. In doing so he vastly elevated their critical thinking skills which led to innovations that helped propel Toyota forward against its competitors.

Taiichi Ohno was unlike most other managers who expect their subordinates to think and do things the “usual way.” Those managers do not comprehend “the usual way of doing a thing” as “always the wrong way” because everyone does it that way except for a few easy-to-ignore outliers like Ohno-san. What is remarkable is the scope of discretion that Ohno-san gave to his disciples, and the confidence that he had in them to help develop, bit by bit, what later turned out to be a new management system. In classical management, most leaders have little confidence in lower-level employees, give them little discretion, and have no interest in abandoning classical management.

In most companies, managers constrain employees’ intelligence, creativity, and ingenuity. Usually, there is a small group of employees, such as those working on new product development, who are less constrained than the mass of other employees and can use their imagination. The constrained employees are taught or are expected to conform to the “usual way of doing a thing,” even though it might be “always the wrong way.”

Lean management has largely been a failure in terms of the fabled “Lean transformation.” It has, however, been hugely successful at adding some new tools to archaic classical management, which is still going strong. The significant change in thinking that Taiichi Ohno pressed his disciples to learn, mostly through the practice of kaizen on the genba, has not been widely replicated because most top managers cannot not do it or will not support it, and lower level managers are unwilling to take the risk of doing it. Instead, managers just go along to get along. Stability for them means instability for others.

If you are driven to think differently, to think opposite as Ohno-san did, then you will have to teach yourself. Start by reading (and re-read) these four blog posts about the books Album of Management Revolution, Taiichi Ohno’s Records: Founder of the Toyota Production System), The Origin of Toyota’s Strength: Taiichi Ohno’s Kaizen Spirit, and Taiichi Ohno and the Toyota Production System as well as Taiichi Ohno’s books, Toyota Production System, Workplace Management, and Just-in-Time for Today and Tomorrow. Take handwritten notes because that will help deepen your learning, organize your ideas, determine your trial and error priorities, and establish your path forward.

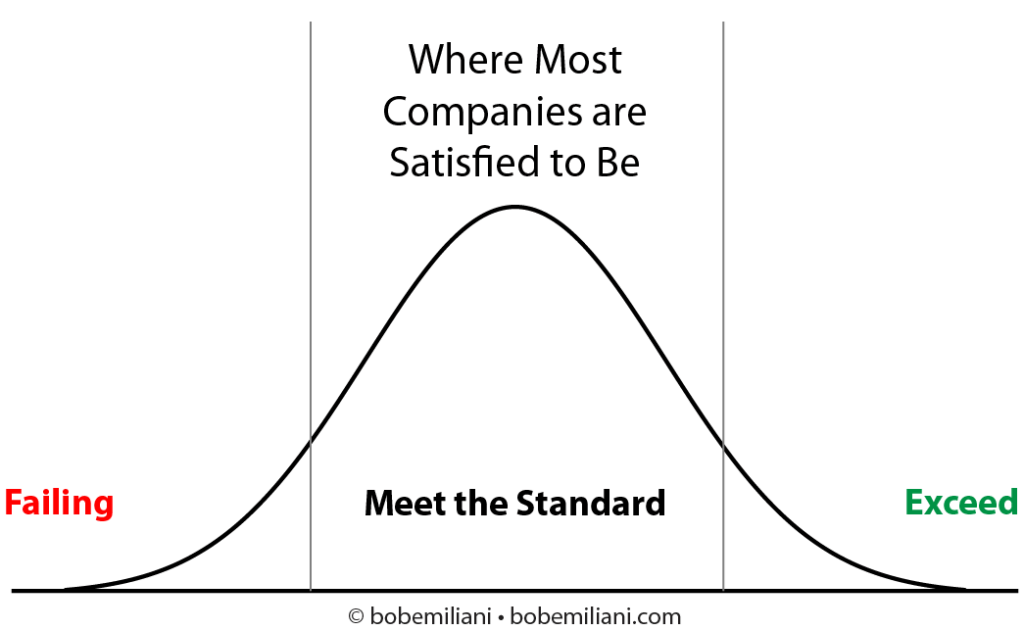

Overall, what have we learned from Toyota’s experience generally and Taiichi Ohno’s experience specifically in creating a new management system? It is the need, in my view, to more fully appreciate how far TPS exceeds the standard (classical management) and, more importantly, how most other companies have virtually no interest in doing that.

It begins with teaching people. Yet most CEOs are satisfied for the company to exist in the middle of the bell curve, despite their public rhetoric, and let others exceed the standard. They reason, not incorrectly, that there is no need to do more than what is expected because that is all that is necessary to be successful, and so Ohno-style teaching is not necessary. To them, “what ever is, is right” and “what exists is what is best.” Most people have that view, not just CEOs.

The leaders of the Lean parade did not anticipate CEOs’ antipathy for progressive management at the start of the Lean era in the late 1980s and early 1990s (the varied reasons for their antipathy are not entirely wrong). This would have been clear had they carefully studied the history of Scientific Management. Furthermore, in their narrowly focused examination of TPS, they did not explore Taiichi Ohno’s remarkable teaching method which was instrumental in creating TPS. While Ohno-san’s teaching method is replicated today in varying degrees by, among others, Shingijutsu kaizen consultants, few people have access to such mind-opening teaching.

I think a lot of people today will say there is no need for understanding what Ohno-san taught and no need to use his genba teaching method. My view is the opposite. It is needed now more than ever. As far as Ohno-style scoldings, those might be necessary too because they force people to think differently.

In conclusion, I have studied Taiichi Ohno’s English-translated writings for more than two decades and found them to be newly enlightening every time I have read them. They’re that good. My view of Ohno-san has long been one of great admiration, and, more importantly, he is the one person who people should listen to most. After reading these four Japanese language books — his lectures and interviews — I have gained an even greater appreciation for his thinking and what he accomplished. My hope is that people turn their attention away from the vacuous Lean luminaries to the one person who started it all, Taiichi Ohno.